Max Heller, full name Maximilian Wilhelm Heller, was unsurprisingly of German descent. His parents Wilhelm and Pauline (nee Slechter) originated from Wurtemburg and emigrated to England before for the birth of their first child Edith at Dover in 1882. Maximilian was the third of five children. The 1911 Census shows that his father was using the Anglicised version of his name, William, and Max had chosen to abbreviate his name in official documentation.

Although Max was to serve at Ryde for only eight years, initially appointed as Deputy Chief Officer and then Chief Officer of Ryde Fire Brigade, and post-August 1941 as Company Officer of National Fire Service, Fire Force 14d, District 2 (Ryde), his service is marked for enduring some of the most testing times of any commander in the district.

In the same year Max’s abbreviated name appeared in the 1911 Census, he joined the Dover Police-Fire Brigade. Unlike Ryde’s failed Police-Fire Brigade experiment (Greenstreet’s Empire), the Dover organisation was long standing and built on a co-operative arrangement that began in the late eighteenth century.

Max’s career began favourably, but then came the First World War. First his parents, who had been living in England for over 30-years, were required to register before being questioned concerning their loyalties. Worse still for Max was that he was ejected from the Police-Fire Brigade, being considered untrustworthy in an official capacity. Somewhat ironically Max was permitted tedious work with the Navy and Army Canteen Board. More ironic is that in June 1918 he was hauled before the Dover Military Tribunal to justify why he wasn’t doing military service. He was clearly trusted by those closest to him – during the war he married Dorothy Watt, daughter of a retired Scottish soldier.

At the end of the war Max, having kept a clean sheet and done what he was permitted to do for the war effort, was keen to pursue an avenue back into the ranks of the Police-Fire Brigade. From contemporary records it seems that his former employers would gladly have welcomed him back, were it not for the meddling of the Dover branch of the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers.

The NFDDSS held up the process for over a year. The Police-Fire Brigade, with post-war vacancies to fill, were as inconvenienced as Max was frustrated. For their part the NFDDSS stopped Max from rejoining without providing any solution to the organisation’s manpower issue. By early December 1919, Max was so exasperated that he decided to hit the matter head-on and wrote to the NFDDSS requesting that he attend a meeting to make his case.

Max’s letter caused a heated debate at the next NFDDSS meeting, held on Boxing Day. So vitriolic was the extremity of the blockers that Vice-chairman Mr O. Mason, presiding, halted the discussion and made the unilateral decision that Max would be invited as per his request to the meeting scheduled for 9 January. Max attended as agreed, joined by Dr Hardman, his solicitor. Such was his appeal, backed by his pre-war record of service with the Force, that to his surprise the Federation made the decision there and then to withdraw their opposition to his reinstatement.

Max may have been able to relax and consider the matter closed, but, despite the Federation’s decision and formal announcement, in April the matter flared up again. This time it was a 23 April meeting of the Comrades of the Great War, held at a club in Waterloo Crescent which erupted into another lengthy and bitter discussion concerning Max’s proposed re-appointment to the Force. The Dover Express reported – the members present strongly resented the action of the Dover Watch Committee in recommending the reinstatement of ex-P.C. Max Heller. This concluded with – a resolution protesting against his reinstatement and asking that an unemployed ex-serviceman should be appointed, who was of British birth. The resolution was passed unanimously. Seven days later it was the turn of the RFR (B) Old Comrades Association to vent their spleen concerning Max’s Germanic heritage with the same proposition and same result as the previous week. However, as the NFDDSS held greater sway, their sanction was seized upon by the Watch Committee and Max was back in the job.

From historical description it is difficult to be sure if the Police-Fire Brigade was entirely or partially integrated, but I’d estimate it were the latter. Max was reinstated as a Constable – a role in which he earned a Chief Constable and Watch Committee commendation within two months of being back in the Force. Within three years he was promoted to Sergeant.

In early 1937 Ryde’s Fire Brigade Committee was contemplating the future command of the brigade. Chief Officer Henry Frederick Jolliffe was 71 years old, a committed fireman with 49 years’ service under his belt. However, concerns had been expressed that he was no longer in possession of either the mental nor physical capacity to continue in the role safely or efficiently. The Committee were equally aware that Jolliffe, appointed as probationary fireman in 1887, was keen to be the first Ryde fireman to complete 50-years of service by remaining in role until December. In an uncommon act of compassion, the Committee, supported by Council, devised a scheme whereby he could be allowed to do so.

The Borough placed an advertisement for the role of Deputy Chief Officer. The FB Committee’s plan was for the successful candidate to be appointed as the Chief Officers deputy, tasked with a clandestine role to oversee incidents and training whilst appearing to be subordinate to the Chief. Several applications were received, including that of Max Heller, described at the time as Senior Patrol Inspector of the Dover Police, concurrent to Second Officer of the Fire Brigade.

Max was invited to attend an interview for Deputy Chief Officer in late April where he stood out as the best of the applicants. After contacting Max to tell him the good news in the first week of May, both the Committee and Max, began making arrangements for his relocation and start date. The Committee breathed a sigh of relief and were eager to get Max to Ryde and in service as soon as possible.

Chief Officer Jolliffe may have lost his sharpness of wit and physicality but was otherwise considered to be in very good health for a man in his seventies. On 8 May he was seen by several in the town going cheerfully about his business. On the following day, while pottering about his home, Glen Rosa in St Johns Road, with no precursor, he suddenly and inexplicably died. Max received the news on 11 May from the Committee, with the offer of an instant promotion to Chief Officer. His Chief Constable also received a communique with a plea to allow Max an earlier than planned departure from Dover.

The Dover Express reported that on 17 September a retirement soiree was held for Max at Dover Fire Station. Evident in the report is that by then Max had already relocated to Ryde and returned to Dover for the event. The well-attended gathering featured Chief Constable Bolt and the Mayor, Alderman George M. Norman. Both lavished praise on Max for his 26-years’ service with the organisation before presenting him with a gold watch upon which was engraved, among other words, the end date of 22 August – presumably his last day of service at Dover. It is a reasonable assumption that in Ryde, Second Officer Williams fulfilled the role of Acting Chief Officer between Jolliffe’s death in early May and Max’s arrival in late August.

In reply to the words expressed about him, and with thanks for the watch, and a framed photograph of Dover’s latest fire appliance, an 8.8 litre Leyland with a 101’ Metz telescopic turntable ladder, Max stated – You have spoken of my success as a Police Officer. Any success of mine is due to the men who were serving when I first joined the Force. They looked after me, and helped me, and saw that I was on the right path. I am proud of those men and for what they did I am grateful. Part of my success was due, too, the authorities having confidence in me. I have to thank all the lads who have served under me for their support and discipline, and especially when occasion arose for ‘dressing downs’ and the sportsmanlike way in which they took correction. I hope that when you go, you go with the same feelings as I - regret at parting with colleagues. There is one other person to whom I have to pay tribute – my wife. We all know that the wife is half the policeman, and her support and encouragement has been an immense help to me. It is now time to say goodbye. It hurts. I wish you all the best. Max also departed on good terms from the district Football Association, where he had long been a reliable and fair referee after his days of goalkeeping came to an end.

A selection of Heller family photographs, graciously submitted for publication by Max and Dorothy's US based granddaughters.

As a younger man Max was an all-round sportsman; be it sports on the field or those more commonly played in public houses. Before his first year at Ryde was over, he had arranged for a collection of pub games to be installed at the fire station. His firemen were delighted and spent more time at the fire station than they had previously – resulting in a greatly improved turnout time during the evenings – precisely as Max had intended. The IW County Press reflected the same in a report of the Brigade Annual Dinner of 5 February 1938, referencing their speedy response during a darts tournament. Mrs Sylvia Needham of the Fire Brigade Committee, a woman on the cusp of becoming a local legend for her indefatigable work as commandant of the Island’s WVS during the war, attended the dinner to award the prizes. After the initial toast to the future of the Brigade by Max, Fourth Officer Charles Gough stood, ordered all present to raise their glasses to their new Chief Officer and stated – Our Chief Officer came to us as a stranger and in a very short time has gained the fullest confidence and support of the whole brigade.

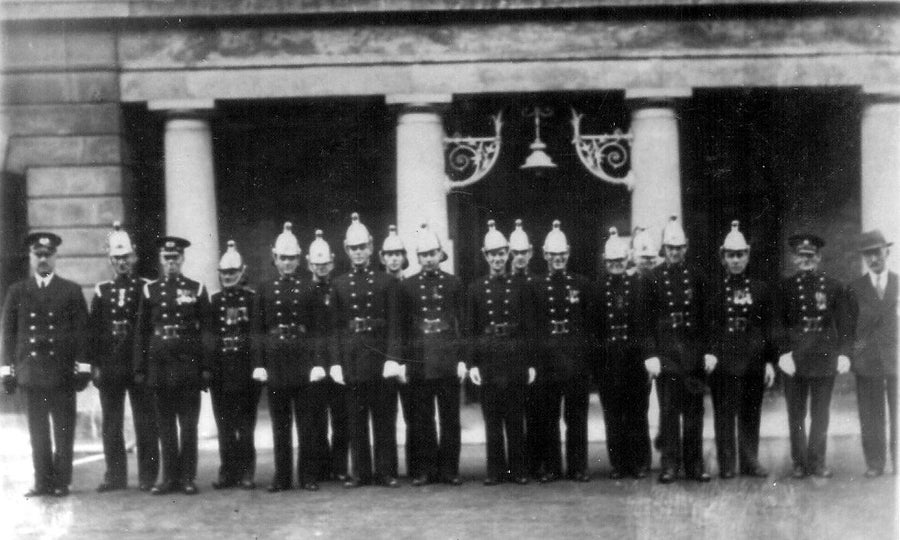

Chief Officer Max Heller (left) with the full strength of Ryde Fire Brigade, 1938.

As world events transpired, in 1938 the needs to prepare civil defence for war began to take up increasingly substantial amounts of Max’s time. As part of the Air Raid Precautions scheme, the Auxiliary Fire Service was created as a separate entity but designed to be attached to regular fire stations, and Max was required to arrange for both recruitment and training. He teamed up with Charley Fowler, the energetic district head of the ARP to carry out several visits for recruitment purposes. District 2, for which Charley and Max were responsible heads of the ARP and fire service respectively, was the land enclosed within an imaginary line drawn from Fishbourne, around Havenstreet, Ashey and out to Bembridge, returning along the littoral to Kite Hill.

Max’s first Annual Report submitted to the Council on 2 July 1938 evidenced the substantial ground he had covered in a little under 12-months, as reported in the IW County Press - 17 fires, including chimney fires, had occurred in the Borough during the year. The Brigade has been called upon to deal with several serious fires. Two of the most serious occurred at Seaview, the first at the Northbank Hotel, where a large building were threatened, and the other at No.3 Seafield-terrace, where a row of valuable houses were at risk. There has been no loss of life through fires and apart from a few minor injuries sustained by members of the Brigade, no persons were injured by burns.

Drills had been well attended and the experiment of dividing the Brigade into two sections to facilitate training proved an unquestionable success. Steady progress had been maintained with the instruction classes, and practical demonstrations with the appliances had been given at every possible opportunity. The alarm bell system had been overhauled and greatly improved by the introduction of a new type of control switches and different pattern accumulators. The introduction of the games room at the Fire Station had resulted in a number of firemen attending there each night in the week, and they were thus instantly available for duty in the event of a call for the Brigade being received.

During the year an order had been placed for a new Leyland turnout, comprising a 60ft. wheeled escape ladder carried on a limousine body, fitted with a 500gpm pump, and a first-aid unit. During the last 10 months the whole of the appliances and equipment had been overhauled. To comply with the requirements of the Air Raid Precautions Act a scheme had been prepared by the Chief Officer for organising an emergency fire brigade scheme to cover the borough and Bembridge. The scheme had been submitted to the Home Office, and it was at present receiving consideration. The enrolment of auxiliary firemen had commenced, and in the very near future training by drills and lectures would begin… It was estimated that at least 100 men would be needed to meet the requirements of the scheme (later this was more than doubled).

Ryde Fire Brigade under the captaincy of Charles Langdon (1888-1895), had been the birthplace of the IWFBF and hosted the first drill competition in 1894. However, the Brigade had seen a pitiable number of successes. The 1938 event was planned for the Big Meade, hosted by Shanklin Fire Brigade. Max Heller took his first opportunity to take the Brigade to a competition very seriously and trained his selected drill team hard. The effort paid off as the five-man team swept the opposition aside to win the Motor-pump drill category and lay hands on the Couldrey Cup.

On 3 October 1938 Max began training the first batch of 28 Auxiliary Fire Service volunteers. In the following April, in recognition of them having completed their training, and to raise interest in the hope of attracting more recruits, Max paraded the AFS firemen through the principal streets of Ryde and other areas within District 2. The IW County Press reported 60 newly qualified firemen in the procession.

Max Heller with the first batch of AFS recruits, photographed in the garden of The London Hotel, 3 October 1938, followed by two images of those that had completed their training parading down Union Street, 16 April 1939.

If Chief Officer Heller wasn’t busy enough, the impositions of the 1938 Fire Brigades Act, receiving Royal Assent on 29 July, had his Town Hall employers in a quandary. Max was compelled to carefully examine the articles of the Act, in cahoots with the Fire Brigade Committee. Having done so, all would have taken comfort in the fact that other than some of the peripheral factors, the existing capacity of Ryde Fire Brigade wasn’t far off full compliance. Politically there was fervent opposition, Alderman Hayden, who had consistently and at times caustically argued against spending money on the Brigade for several decades, raised in Council that the cost of full compliance would raise the Brigade annual rate from 1d to 3d. But this time his attempt to retard the progress of firefighting capability was impotent as it was statutory, not an option. The overbearing questions concerned the AFS – where to accommodate the men and equipment, provision of uniforms and the appointment of officers to oversee them.

Among the accommodations identified for the AFS was the requisitioned Stainer’s Dairy Yard in Edward Street. The substantial cluster of rooms, garaging and the open yard featuring a well, were subject to basic modifications to enable its use as both an operational station and district training centre. Under the direction of Max Heller, it was the AFS volunteers themselves that gave up their time to convert one part of Stainer’s into a games room. Since 1937 Max had administered the brigade from a bureau at his home - the additional capacity at Stainer’s allowed him to establish an office.

In March 1939 a reporter of the IW County Press sat in the public gallery while the Council progressed through its business.

The reporter detailed the content, and the mood, when it was raised that Chief Officer Heller had asked that attention be directed to the exceptional increase in work over and above the agreement made with him when he was employed as a part-time officer in 1937. His status remained part-time and his recompense unaltered, whereas his scope of responsibility had increased ten-fold and was steadily increasing.

The Fire Brigade Committee revealed that they had discussed with Max a scheme of pay which included modifying his status to that of full-time Borough employee, to which Max had agreed pending Council resolution. In presenting the proposal to Council, the Committee were shot down in flames by Mr Spate – the recommendation is illogical… from the ridiculous to the sublime – and Alderman Hayden, having identified an element of fire brigade progress that he could impede without opposing the law added – During 44 years in public life I have never known such a recommendation be brought before a Council! Despite the knock back Max continued regardless, working full-time hours, and some, for a part-time wage.

The 29 April edition of the County Press included a brief message from Chief Officer Heller to all persons in the district to advise him of any available off-mains open water supply in order to draw up an overlay to the hydrant map. In July Max joined ARP officers to design, organise and implement an expansive civil defence exercise. Based on the premise of a gas-bomb dropped on Bedworth Place, a cast of almost two-hundred included volunteer casualty actors, AFS firemen, ARP wardens, rescue, and decontamination squads alongside members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment and Women’s Voluntary Service. As responders deployed and their skills tested, the scenario developed further with a second gas-bomb in Edward Street, affecting the AFS fire station, followed by an incendiary bomb strike on the main fire station in Station Street. At its conclusion Brigadier General H.E.C. Nepean, the umpire, expressed his congratulations to all both for their performance, and for its innovation.

Some of the AFS volunteers involved in the training were part way through their initial 64-hour course under Max’s direction. After completing the program Max ensured objectivity by having his trainees examined and tested by officers from other brigades. The first to pass received their badges and gratuities from the Mayor at a ceremony held at Edward Street on 13 August 1939.

Max Heller with 'Ethel' the 1938 Leyland appliance, marked 14D2Z1, in refence to its callsign during the NFS period.

Through the stagnancy of the Phoney War Max had to continually justify the number of AFS firemen required to run his scheme, as approved by the Home Office. He wasn’t alone. Across the Island and elsewhere in the country Chief Officers of brigades and local heads of the ARP were being hammered by local authorities for the continued cost of a raft of rescue employees who, at that stage, had not been required to lift a finger in anger. External pressure was exerted from various ratepayers’ associations, angry that the rates had been substantially raised to fund the ‘army of dart players’ or ‘draft dodgers’ as the AFS and ARP began to be tagged. Central Government funded approximately 75% of the cost, but the remainder had to come from local wage earners. By the fourth month of 1940 local authorities were plaguing the Home Office with requests to reduce the strength of the emergency personnel, and some reductions were permitted in rural areas – and then the London Blitz began.

Even those areas not directly targeted were not safe. Hastily departing bombers unleashed undeployed payloads indiscriminately across the south of England in a hurry to return to the vanquished airfields of northern France. The first bombs to fall on the Island occurred in the night of 16 June 1940. A lone unidentified bomber dropped two high explosive bombs on Chale golf links. Windows were shattered up to 200 yards away, but no casualties were occasioned. But it was the start, and a shock. Slowly but surely the random visitations increased, until some became deliberate. By late 1940 the intensity of attacks, particularly those limited to the incomparable efforts required to deal with outbreaks of fire caused by the cheaply produced and liberally deployed 1kg incendiary bomb, had changed the public outlook of their expanded emergency services.

One of Max’s men wrote in his diary after an intense incendiary raid on the St John’s area of the town that stretched the Ryde firemen to their limits – The Public still regarded us as three-pound-a-week army dodgers. Overnight the position changed, and we were proud to walk the street in fire service uniforms. Above all people commented in letters to the press and direct to the service, of the skill, tenacity and courage of Ryde’s firemen under fire. All of this, the organisation, the second nature adoption of procedures and skills, was down to the scheme created by Max Heller.

But when Max’s pay again came up for review in March 1941, the Council still refused a raise. Remaining the consummate professional Chief Officer Heller didn’t allow one jot of his personal disappointment to affect his performance as the head of firefighting in District 2. Max was appointed to a full-time salaried role when the National Fire Service was formed in August 1941. However, the NFS favoured young commanders and effectively demoted Max to Assistant Company Officer subordinate to C.H. Pratt, a former East Cowes fireman. For unknown reason, Pratt was returned to East Cowes two months later and Max was again in charge as Company Officer of District 2 (one of few of the elder pre-NFS Chief Officers to remain in command on the Isle of Wight).

His leadership was never in doubt and came to the fore alongside so many of his contemporaries during the Isle of Wight’s toughest test – the Cowes Blitz of 4/5 May 1942. Max and the men of Ryde, attended East Cowes where, among several moving and changing priorities, they were tasked with preventing destruction of the East Cowes gasworks. Materials and a structure adjacent to the gasholder was blazing furiously, threatening the integrity of the holder which if penetrated would have resulted in catastrophe. Under Max’s command his firemen, courageously assisted by a member of the Home Guard, battled the flames from the only available location – a tight passageway that was continually logged with clouds of dense hot smoke. Max knew that breathing apparatus was required, but wasn’t available, and going against his firefighting instinct the needs of the task compelled him to join his men to keep them returning to the fire-front between bouts of withdrawing to fresh air to recover.

One fireman collapsed, his lungs overcome by the fumes, and was dragged into the street. Inhaling clean air revived his system and he didn’t hesitate to rejoin his colleagues at the branches as they pushed further into the seat of the fire. Inch by inch they battled forwards, knocking back the flames and creating a water-screen between the fire and the gasholder. In the aftermath Section Leader Hannam submitted a report commending two of the firemen for their actions, supported by Max and Divisional Officer Charters, the two were awarded formal commendations from the Treasury Committee on Civil Defence Honours.

When the sun rose at 06:33 daylight illuminated the devastation around them. With NFS reinforcements still waiting conveyance across the Solent, the Island’s firefighters had no choice but to continue with their labours. During the bedlam of the night Max was compelled to detach his Sub Officer Albert Harry Collis with a crew to another sector.

Around 08:00, as reinforcements began to arrive and relief crews were organised, Max was accounting for his firemen. He relocated his Sub and asked if he’d seen Leading Fireman Dewey and Fireman Weeks – he hadn’t. Max tasked Sub Officer Collis to seek them out – a journey that led him across the Medina to Northwood where the bodies of those fallen were being assembled and a mass grave was being prepared.

Sub Officer Collis returned to East Cowes and advised Max that Dewey and Weeks were among the dead, but that he’d arranged for them to be separated and not placed in the mass grave. When relief crews were finally despatched to take over from the men of Ryde at 11:30, Max ordered Sub Officer Collis to return to Ryde with the men. Then Max crossed the Medina heading for Northwood. After paying his respects to his two lost in action, Max arranged transportation and travelled with them, refusing to leave the fireground until the last of his men had been returned to Ryde.

Leading crews of happy successful firefighters is not a difficult task. Leading them in the aftermath of such a lifechanging experience from which two of their colleagues lost their lives would represent a challenge for any leader, even one of Max Heller’s experience.

Throughout the war there was a steady migration of personnel to and from the IW division of the NFS. Divisional Officers, Company Officers and all ranks including firemen were moved, relocated, or detached. The most predictable aspect of NFS life was that nothing stayed the same for long – with the exception of Max Heller. He remained a rock in the life of District 2’s firemen.

In March 1944 at 58-years old, Max’s health failed him, compelling his retirement from the NFS. He remained resident at Milligan Road, Ryde.

After Victory in Europe, he was feeling a little better and decided to spend his free time reacquainting with former colleagues in Dover. On 21 June he departed Dover on the boat train to Charing Cross. When the train pulled into the station he was discovered collapsed in his carriage. He was taken to the nearby hospital and immediately pronounced deceased.

Reporting his sad and untimely death the IW County Press eulogised – Extremely conscientious, with a deep sense of loyalty, he was a good disciplinarian and a trusted leader who won the affection and esteem of the large body of men and women who served under him and whose comfort and welfare he studied. Under his capable leadership the brigade was reorganised to a high standard of efficiency. On the outbreak of war Mr Heller redoubled his energies and the high qualities of his organising abilities were reflected in the recruitment and training of the Auxiliary Fire Service.

Six days later Max’s funeral was held at Holy Cross, Binstead, his coffin born by six NFS members of District 2. His body was interred at Cemetery Road.

After the war, Max and Dorothy’s only child, Douglas Max, who preferred to be known as Max, emigrated to the United States where he was to establish a successful career with the Lockheed Martin aerospace company, rising to the position of Director of Aerospace Research. At Douglas’s behest Dorothy crossed the Atlantic to spend the remainder of her life with her son, daughter-in-law and three granddaughters. Dorothy died in August 1964. Douglas arranged to have her body returned to the UK so that she could be laid to rest with Max. Accompanying his mother’s body to the Isle of Wight, after the funeral Douglas made arrangements, accompanied by cash payment to persons unknown, for the installation of a headstone bearing the names and details of his parents. To the shame of that unscrupulous individual the cash was taken but no headstone supplied – Max and Dorothy’s grave remains unmarked to this day. In recent years I have been in contact with all three of Max and Dorothy’s granddaughters in America. They were able to tell me of their father’s sadness when he visited the grave many years later and found it unmarked. A sad epitaph to the story of one of the Island’s finest fire officers.

Douglas, Dorothy, and Max Heller.

If you have enjoyed this page, why not make a small donation to the Firefighters Charity.