For many years my wife Sharon and I have researched the histories of our respective families. This revealed far more than either of us ever expected, including a raft of ancestors of whom we had never heard of before. On my side, of which I have multiple streams due to being adopted, I discovered that including myself and my Dad, every direct line male ancestor of the Corr’s had served for varying lengths in the British Army right back to my third great grandfather, John, who fought in, and survived, the 1815 Battle of Waterloo with the 32nd Regiment of Foot.

I discovered that my great grandfather, James, survived the largely forgotten four-month Siege of Ladysmith during the Second Boer War. Had he not, this line of the Corr family would have never existed. And therein lies my fascination with family history – those tantalising moments in world history involving family members that either extended or chopped a branch of the tree.

On Sharon’s side her father was a West and her mother a Caws, a well-known family name in the district of Seaview and Nettlestone. The naming of Caws Avenue is a modern nod of deference to a family that once owned much of the land and greatly influenced its development and prosperity.

In the course of researching Sharon’s expansive and fascinating ancestors we discovered one Stanley Winther Caws, her third cousin three times removed. His date of death alerted us to the possibility that he was killed during the First World War. This proved correct, and what it led to was the discovery of one of the most incredible if brief lives of a man very much of his era.

This task wasn’t entirely ours alone and our appreciation is expressed to a few very willing and helpful kindred souls located in Canada and South Africa.

What follows below is what we discovered of the incredible life of Stanley Winther Caws.

Beginnings

It was Saturday 22 March 1879. Oscar Cottage in Seaview High Street was alive with the moans and cries of a woman in labour. Harriet Caws (nee Handley) was the wife of Douglas who waited patiently in the hope that his wife would deliver a son and heir to follow four-year-old daughter Dora and her younger sister Hilda.

A son was born.

Seaview suspension pier. Completed two years after Stanley’s birth by another of the Caws family.

Douglas was an agent of estates and commissioner for oaths. Harriet, seven years his junior, spent her time enjoying ladies leisure's and sharing in the care of her children with residential maid Ada Bartlett. They enjoyed an affluent life in a quiet corner of the Island about to explode in popularity for the wealthy and aspirational.

Seaview didn’t exist as a functioning village until the early 1800’s. In the opening decades of the nineteenth century the tract of land was divided into nine parts, six of which were acquired by gentlemen bearing the name Caws. All six of them, like their fathers before them, were skilled and renowned pilot boat masters including Robert, who with his wife Elizabeth (nee Goodall) produced several children. In the middle of their brood was Silas born in 1812. He too took to the seas and so successful was he that his wife Emma proudly entered her occupation as pilots wife in the census return. Profiting from his success Silas built Coronation Cottage in 1838.

Silas and Emma were to have eleven children – eight sons and three daughters. Douglas was their second eldest, born 23 August 1843. Douglas wasn’t to follow his ancestry to the shore and was located in the 1861 Census lodging at a house in St Mary’s Street, Cowes, earning a living as a grocer’s apprentice. Ten years later he was back in Seaview, sharing Oscar Cottage with two of his sisters, Emily, and Eliza. His career prospects had taken a significant turn, he was practising as a house and land agent.

On October 11, 1873, he married Harriet. Six years later their first, and only son, arrived and was named Stanley Winther Caws. Stanley was followed by two more daughters Constance and Alison.

There is no evidence upon which to paint a picture of Stanley’s childhood at home, but thanks to the archivist of Portsmouth Grammar School we know a little of his education. Having discovered this article in March 2025, the archivist contacted me with the following - Stanley attended Portsmouth Grammar School, joining as a 12 year old on 8 January 1892. He took part in Sports Day races, including the three-legged race in which he came 11th. He also competed in under 14 tug-of-wars against other schools. His best academic subjects were English in which he was top of the class, and Geography in which he was third. His address is given simply as Seaview, I.W. I can't see a date for leaving but it looks like he wasn't at PGS the following academic year.

It appears from his choice of profession that his father did not possess the spirit of adventure present in his predecessors, perhaps it skipped a generation and remerged in the spirit of Stanley. The Census of 1901 evidence that Stanley had left home and was lodging in a first-floor bedroom and parlour at 32 Wellington Road, Charlton, South-East London. He afforded his rent and other needs by working as an electrical engineer.

This was during the era of Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and Werner von Siemens, among others, who evolved a scientific curiosity into an essential tool for modern life. London would have literally buzzed for the power source and Stanley’s pioneering instinct led him to the centre of its activity.

In 1901 London was buzzing for another reason.

The Second Boer War

When the 1901 Census was taken on 31 March, the country had been at war with the South African Boers for over a year (for the second time in twenty years). By June 1900 and the fall of Pretoria, the British strength in conventional battlefield warfare had overwhelmed the Boers. It had been a difficult and costly conflict with some humiliating setbacks in the opening weeks of late 1899, but those in the British camp who considered the conflict to have been decided by their victories in 1900 were wrong. The highly motivated and mobile Boer forces restructured to adopt tactics of insurgency, foxing British commanders through ambush, interdiction, and precision assault, fleeing the scene of each action before British heavyweight infantry and artillery units could be assembled and brought to bear.

The conflict throughout had received more attention from press photographers than any before in the history of the world, and most notably, was the very first to be captured in moving images. A steady stream of reports, photographs, artist sketches and footage were transported home to feed the voracious appetite of a public ennuied to imperial expansion, reinvigorated by the silver screen images of its soldiers on the front line.

Resident in London, Stanley would have been exposed to sufficient media to have become as well informed as any of the progress of the war. Those with the knowledge and perception to do so, would have recognised that by spring 1901 British forces needed to adopt tactics commensurate to the new threat.

A Commando of Boer farmers at Spion Kop, Natal.

Imperial Yeomanry

Over a hundred years earlier in 1794, the Government of the day feared invasion by the French Revolutionary Army. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger passed a bill that invited Lords Lieutenant of counties to raise voluntary cavalry units. The units were to act as a quick reaction force able to deploy at speed and counter an invasion from wherever it arrived.

This gave birth to the Yeomanry recruited on lines of clear class delineation. They weren’t gentlemen but they were considered a cut above the rest, being country men who farmed as freeholders and in some cases tenant farmers.

When the Second Boer War began in 1899, the Yeomanry existed as originally intended, for home defence only. In the opening period of the conflict the British Army suffered a series of crushing defeats, inspiring press sources to headline reports Black Week. The Government was pressured by the military to deploy more troops to South Africa and consider methods of combatting the battlefield speed of the Boer sharpshooters, skilled in accurate rifle fire from the saddle after decades of hunting across the veldt.

They needed horsemen in numbers and the Yeomanry afforded a quick fix.

A revision of regulations allowed the Imperial Yeomanry to be deployed overseas in the service of the Crown. A total reorganisation followed. Existing yeoman, who had never seen action but nevertheless considered themselves veterans, were incensed at the order to discard their swords for rifles as the IY was to lose its cavalry status and operate as mounted infantry.

The first contingent of rifle bearing Yeomanry was to depart in a steady stream of ships from January to April 1900. The change of Boer tactics and an increasing need for mounted troops, added to the awareness that many of the first contingent of gentlemen troopers were approaching the end of their 12-month contracted service, compelling a second recruitment sweep in early 1901 under Army Order of 17 January.

Paget's Horse

George Thomas Cavendish Paget (Fig.1) was the son of a British general and a compulsive self-styled soldier and adventurer. Never having served as a regular soldier Paget had earned combat experience by placing himself in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, the Zulu War of 1879, and the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, in addition to several smaller conflicts and callings of an adventurous nature.

Paget was one of a number of similar men, contemporarily described as enthusiasts, that formed additional units that aspired absorption into the Imperial Yeomanry. Paget recruited largely from upper middle-class members of London’s gentlemen’s clubs and that of professional men. As recruitment neared completion Paget’s Horse was accepted as the 19th Battalion IY comprising four companies, 51st, 52nd, 68th, and 73rd. However on condition of service Paget was forced to accept the position of second-in-command with the temporary rank of Major.

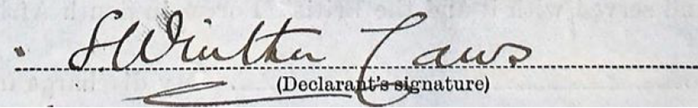

When, where, and how Stanley became aware of the call to arms of the Yeomanry we shall never know, but clearly it appealed to his sense of adventure and on 23 January 1901 at an unspecified address in London’s Carlton Street (most likely the Carlton Club) Stanley signed a short service attestation for one years’ service with 68th Company, Paget’s Horse. Close to Stanley’s details in one of the many rolls that survive is the name of Fernand Charles Butler of Frome, Somerset. The pair were set to become close friends.

Left - an extract from the Isle of Wight County Press, 9 March 1901.

Through research no direct references to the South Africa service of Trooper Caws No.20347 has been unearthed. However, Cosmo Rose-Innes, an adventure seeking barrister of the Honourable Society of Gray’s Inn, wrote and published With Paget’s Horse to the Front, shortly after returning home.

From Rose-Innes, and a few other references including Trooper 8008 by the Honorable Sidney Peel, we can be confidant that Stanley attended basic training at Chelsea Barracks. This was supported by two-days a week in horsemanship at Knightsbridge Barracks and courses of musketry at Bisley Ranges.

Following acquisition of the necessary skills and manoeuvres Stanley boarded SS Tagus (below) on 16 March and disembarked at Cape Town (photographed below in 1898) on 4 April.

The battalion gathered at Maitland Camp (two images of the camp below) outside the city while waiting for their horses, wasting no time by continuing training in the conditions of the veldt. With the horses safely disembarked, a thirty mile move and brief stop at Stellenbosch preceded a rail journey of over 500 miles to join Lord Roberts’ main army on the Orange River. On 4 May Roberts placed Paget’s Horse with General Sir Charles Warren’s column, tasked with suppressing the Boers in Griqualand West and the Bechuanaland Protectorate.

The IY part of the column, consisting of Paget’s Horse, and the 23rd (Lancashire) and 24th (Westmorland and Cumberland) companies of the 8th Bn, were commanded by Charles Hay, the Earl of Erroll. Warren began his advance before all the troops had assembled and entered Douglas on 21 May. Paget's Horse followed behind. The Boers were at Campbell, blocking the route up onto the Kaap Plateau.

On 26 May Warren's column camped at Faber's Put, a farmstead a few miles south of Campbell where he prepared to assault the position. He ordered two companies of Paget's Horse up to cover Schmidt's Drift on the Vaal River by 30 May to prevent the Boers escaping north-westwards, while another detachment of 52nd Company under Lieutenant J.G.B. Lethbridge escorted the column's supply convoy up from Belmont; this arrived on 29 May. Warren had placed insufficient pickets and before dawn on 30 May a force of Boers surrounded the camp at Faber's Put, infiltrated into the garden, and prepared to attack. Spotted by a Yeomanry sentry who fired on them, the Boers fired back, and a furious firefight ensued, while the Boers stampeded the Yeomanry's horses and shot down gun crews.

The 23rd and 24th IY Companies advanced to support their picket on the southern ridge and brought their two Colt machine guns into action. The small group of Paget's Horse protected the machine guns while the rest of the IY advanced by rushes over open ground towards the ridge and drove off the Boers. The Boer force rode off before the Yeomanry could recover their own horses. Lieutenant Lethbridge was among the casualties, his left forearm being shattered, and Trooper Mather was mentioned in despatches for bringing Lethbridge in under heavy fire. Following the action at Faber's Put Warren was able to clear Griqualand West without further trouble, the column entering Campbell and then Griquatown.

After the action Paget's Horse continued guarding Schmidt's Drift and escorting supply convoys from Kimberley for the column, which camped at Blickfontein. When Warren moved on, a detachment of Paget's Horse escorted the Royal Canadian Artillery's guns from Faber's Put to Schmidt's Drift. The concentrated battalion then marched from Schmidt's Drift to Kimberley for rest and refitting before entraining for Mafeking.

Lord Roberts now decided that his isolated garrisons were a waste of manpower, and he ordered most of them to be evacuated. In early July Warren sent Erroll with a column, including Paget's Horse, to relieve Klerksdorp, but it had surrendered to the Boers on 25 July before he arrived. So he continued to Lichtenburg, taking away the garrison there. Paget's Horse marched through hostile territory from Mafeking to Lichtenburg, posting advance, flank, and rear guards, and having daily brushes with small detachments of Boers. Erroll then marched through Ottoshoop to join Lt-Gen Sir Frederick Carrington at Zeerust on 2 August. Carrington's column had come down from Rhodesia to evacuate some of the isolated garrisons in Western Transvaal. Carrington marched the combined force towards the Elands River to cover the retirement of the garrison at Brakfontein. The column was hampered by long train of empty ox-wagons to bring away the supplies at Eland's River, and there was a running fight with the Boers. The action was described by Rose-Innes:

We galloped about from place to place the whole morning without firing a shot, although all round us our guns and pom-poms were throwing a continuous stream of shells, and we could hear the crack-cracking from the opposite kopjes. We were not, I think, under actual fire altogether for more than an hour, although the engagement itself lasted all day.

After this inconclusive engagement, Carrington gave up the attempt to reach Brakfontein and returned to Mafeking. Paget's Horse had to fight a dismounted action to clear a Boer force blocking the road back, and Major Paget was slightly wounded. Paget's Horse went back to its camp at Ottoshoop and spent the following weeks patrolling the road between Zeerust and Lichtenberg, fighting three separate engagements with parties of Boers.

In one of these Paget's Horse had to saddle-up and gallop out of Ottoshoop to relieve a detachment of the Victorian Rifles pinned down on a kopje. On arrival they dismounted and fired volleys of suppressive fire at the Boers hidden on the opposing kopje, until the Boers withdrew.

A large detachment of Paget's Horse was sent by train to Vryburg to join a relief column for Schweizer-Reneke, which was being besieged by the Boers. The march was unopposed, and the unit spent a few days patrolling the surrounding country, experiencing a few contacts with small parties of Boers. Paget's having returned to Vryburg, the Boers once again besieged Schweizer-Reneke. This time the unit had to escort a slow convoy of oxcarts, taking a week to cover 35 miles. After two such convoys, the detachment returned to the rest of the battalion at Mafeking.

By January 1902 Stanley’s year of service was up, but unlike the majority he committed to further service, not returning to Britain until 18 August, long after the war ended with the Boer surrender and the Treaty of Vereeniging signed on 31 May.

He returned with wound scars on the rear of his right shoulder and left arm and with both forearms heavily tattooed.

What would become of such a man of adventure on his return to London? To return to the modest rented rooms in Charlton and an occupation of electrical engineering may have lost its appeal after the freedom of galloping across the sun-bleached veldt armed and ready for the fight.

Where life took Stanley for the years immediately after the war isn’t known, but from 1905 he repeatedly appears in passenger manifests of vessels crossing the Atlantic between England and Canada. In several of them Stanley is joined by Fernand Charles Butler, his comrade and fellow trooper of the 68th.

In the same year that Stanley began his visits to Canada, the Legion of Frontiersmen was formed in London.

Legion of Frontiersmen

The Legion of Frontiersmen was formed by Roger Pocock (Fig.2).

As a young boy Pocock emigrated to Canada with his family when his father took the Holy Orders and set off to the New World with hopes of educating the savages of the north to the ways of Christianity. Inspired by his father Roger also undertook missionary work when reaching adulthood. However other interests proved his weakness, and the church disengaged his services due to notorious philandering.

In 1898 Pocock led a failed expedition to run horses to the Klondyke. While there the finger of suspicion pointed at him for the robbery and murder of Sir Arthur Curtis, whose body was never found. After slipping the net of controversy Pocock departed Macleod in Canada and rode solo all the way to Mexico City along the Outlaw’s Trail. From South America Pocock crossed the South Atlantic and arrived in South Africa just in time for service in the Second Boer War with an unspecified unit contemporarily described as one of the most irregular bands of scouts.

After the war Pocock returned to Canada. Free of the suspicion of Curtis’s murder by Mr Justice Gorrell Barnes who accepted the suggestion that the missing man’s disappearance was by his own act or omission, Pocock was appointed to the North West Mounted Police. Pocock relished the position until 1904 when the Illustrated Mail paid him to travel to Russia and report on the Russo-Japanese War. On his return the despatches he’d sent and information he’d obtained proved of great interest to Prince Louis of Battenburg, Director of Naval Intelligence.

In the following year, buoyed by the adventure and success of his Russian encounter and the appreciation of intelligence circles at home, Pocock formed the Legion of Frontiersmen.

Prompted by fears of an impending invasion of Britain and the Empire, the Frontiersmen, a civilian organisation that never achieved official recognition, was founded to be a field intelligence corps that would watch over and protect the boundaries of the Empire. Headquartered in London, the Legion of Frontiersmen formed branches throughout the Empire to prepare enlistees for war and to foster vigilance in peacetime.

The Volunteer Bounty

I was very fortunate to have acquired a copy of West of the Fifth from Canada. Very few copies were produced and despite this being well read and tatty it is a valuable addition to the research into Stanley's life.

As mentioned above, from 1905 Stanley made several transatlantic crossings, often from Liverpool to ports of Nova Scotia. Clearly the rugged opportunity of Canada’s sprawling wilderness caught the imagination and his adventurous spirit.

Extracts from West of the Fifth, published by the Lac Ste Anne Historical Society in 1959 refer directly to Stanley and his companion Fernand Charles Butler.

After the Boer War 1899-1902, numbers of Englishmen who had taken part in the campaign came out to Canada, and our Municipality received her share of Boer War veterans.

Butler and Stanley Caws were in the country west of Lac Ste. Anne in 1906, and may have put in squatters stakes on the land in the Stanger area where they later filed on homesteads, but had no shacks or houses up until well into 1907. A Dutch pioneer settler stated, “I often met Caws and Butler, our nearest neighbours for a long time. In those days 12 or 14 miles was very close.”

A club was formed by the young men around Lac Ste. Anne – homesteaders, as well as packers, surveyors, and freighters. They called themselves the ‘Legion of Frontiersmen’ and met together for good fellowship. On occasion they came up as far as Caws’ shack at Stanger for a meeting. They built a hall at Lac Ste. Anne as a club room and for parties and dances.

Several other references expand on this, and claim Stanley was the first Commandant of the Alberta branch of the Legion of Frontiersmen.

One includes the following revealing extract – This early era commandant, was recorded as Caws, Cawes and Caus. He was a tattooed Boer War veteran and a ‘remittance-man’ (often the ‘black sheep’ paid by the family to stay out of England) who formed the first Legion of Frontiersmen unit in Alberta.

The Edmonton Bulletin edition of 23 May 1907 referred to Stanley and Fernand providing an insight to the type of life they lived on the frontier of Empire – Messrs. Caws and Butler, who have been land seeking around Lac Ste. Anne, arrived here Sunday evening and stated that while camping near Jack Fish Lake, 17 miles further west, the horses attracted their attention by their startled antics. On going to see the cause they found a big she bear standing about six feet high and three cubs with her. A volley of shouts instead of shots was heard. As hard luck would have it neither possessed a gun. The whole outfit made tracks for the bush, twigs and sticks flying in all directions.

If it is accurate that Stanley and Fernand had placed squatters stakes around land in 1907, the news that broke in the following year would have been music to their ears.

Under the articles of the Volunteer Bounty Act of 1908, veterans of the Boer War were entitled to 320 acres of Dominion Land. Stanley wasted no time to post his formal application under the Act to the Secretary of the Militia Department at Ottawa on 16 February 1908 and signed on the dotted line.

With checks processed, Stanley’s application was successful. Later in 1908 he made a brief return to England for reasons suspected to have been in connection with the Legion of Frontiersmen. He didn’t dwell for long. Whether or not he paid a visit to family on the Isle of Wight is not known, and may not have been welcomed as a remittance man. The passenger manifest for his return voyage states Returning Canadian, suggesting that he was by then naturalised to his chosen land, declaring his occupation as cattle rancher at Stanger.

Returning to Alberta, Stanley epitomised the work-hard, play-hard maxim to the full – gritty pioneering coupled to bawdy frolics were his daily diet.

One extract from West of the Fifth suggests a touch of philanthropy in the recollections of a fellow frontiersmen – I stayed in that neighbourhood about three years. The last year I was there was a very dry year. In the late fall a fire swept the country. That same fire burned and kept eating away at the top soil during the winter. The soil on my homestead was completely ruined and by writing to the Department I was allowed to file on another quarter located in the place that some years later was called Stanger. While I was staying at Barker’s I often met Caws and Butler, our nearest neighbours for a long time. When I changed locality, they persuaded me to settle near them. Those first years in Stanger were hard ones, money was scarce and the art to make a lot out of a little was not acquired yet.

In 1908 Oswald Norman, Tom Geurrier, and Mr Mallandaine came together to the Stanger district. A young man, Strickland by name, and a friend of Stanley Caws, also came at the same time. Young Strickland met a sad fate. He was a fine young man but had never roughed it. It was remembered by some of his acquaintances that when he left England one of his aunts gave him a hot water bottle for a farewell gift. He stayed a lot with both Caws and Norman in their shacks and they were kind and friendly to him, but he was very independent and didn’t like people giving him his keep.

Stanley Caws devised a scheme – he got old Mr Butler to have Strickland do chores for him and Caws paid Butler his ‘board bill’. But Caws told Butler on no account to ever let Strickland know about the board being paid; to let the young man think he was earning his board. However, one day in a huff the old man stupidly let it out, and that was when Strickland disappeared. He left a note to Norman leaving him his few belongings. They searched for several weeks and finally found what was left of him with a phial beside him. He had taken poison. It was a tragic affair.

Land Grant chart of Lac Ste. Anne district in 1914. It is known that Stanley owned six of the small squares, but which ones have not been identified. While the map carries no scale, an estimate can be made when considering that Lac Ste. Anne near the top right, has a surface area of 21 miles. Although not clear, the homestead of Stanger can be seen to the upper left.

For Stanley life was never dull. From 1908 until 1914 he laboured to profit from his six plots of land whilst variously serving with the North West Mounted Police, as Corporal of the Legion of Frontiersmen, took an entrepreneurial interest in various business opportunities, and served as a Senior Non-Commissioned Officer in the 19th Alberta Dragoons. Some attribute the formation of the 19th Alberta Rifles to the Legion of Frontiersmen while others dispute this.

What is inarguable is that the unit, formed in Edmonton in 1908, was retitled the 19th Alberta Dragoons, a unit of mounted militiamen, on 3 January 1911, perfect for a former Yeoman who’d fought in action as a mounted infantryman with Paget’s Horse to be immediately appointed to Sergeant. His closest friend Fernand Butler joined as a Corporal.

Not one to dwell on an opportunity, Stanley turned his attention to domestic matters and submitted a patent in the United States, accompanied by sketches, for a gentleman’s Combined Closure Cap and Styptic Holder. Patent was pending for some time until granted in early summer 1915, followed by an article in the Scientific American.

Stanley almost certainly never got to see the grant or the article as the clouds of war had gathered over Europe taking him in an entirely new and unexpected direction.

Preparation for War

On 4 August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany. Within days a Bill was passed enabling formation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The CEF existed as a modest formation until the call-up began in January 1915. The Dragoons were mobilised for home defence four days after the declaration and in less than a month were being readied for an Atlantic crossing with the 1st Divisional Cavalry.

Stanley and Fernand departed their homesteads and headed east to form up with the Dragoons at Valcartier, Quebec, on 23 September where they attested to the CEF. Stanley signed documents describing himself as an unmarried prospector that refused all inoculations. Standing just over 5’ 11” tall with a fair complexion, hazel eyes, and brown hair he stated his faith to be that of Christian Scientist, although other contemporary documents state Church of England.

In early October, the 19th Alberta Dragoons began their voyage amid a flotilla of ships bound for the mother country. The armada took precautions against U-boat attack and weren’t inconvenienced until the south-west coast of England came into view. An unplanned disembarkation at Plymouth was enforced due to Imperial German Navy submarine activity around the Isle of Wight and Portsmouth. The tricky and protracted process of alighting was followed by movement and encampment on Salisbury Plain.

Salisbury Plain isn’t the most appealing of destinations in any winter, but the winter season of 1914 was noted as one of the wettest in the history of the district. Day after day under incessant rain CEF units arrived, pitched their tents, and furthered the extent of the quagmire. Frontier men used to the rigours of life in the wild of Alberta were left disconsolate and despairing with an inability to keep anything from saturation. Many fell ill while Officers and NCO’s attempted to instil discipline and motivation through drills and manoeuvres that served only to add to the utter devastation of the ground, soaking of uniforms and caking in mud.

It is hardly surprising that some looked for alternatives.

Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps had existed for only two years when European hostilities broke out and was to prove a vital arm despite the statement by French General and military theorist Ferdinand Foch that aviation is a good sport but for the army it is useless.

How Stanley learned of the RFC from his mud encrusted encampment on the Plain isn’t known, but he did, and the London Gazette of 26 March 1915 reported that Stanley, who had just turned 36, had been struck off the strength of the Dragoons and appointed as Second Lieutenant (on probation) with the Flying Corps having already attained his Great Britain Royal Aero Club aviators certificate at Brooklands in February.

On 7 May, with his wings intact following further flight and aerial combat training, Stanley was appointed to 10th Squadron, 1st Wing, RFC. During part of this period he was billeted at the Blue Anchor in Byfleet. He was by some degree the eldest of the crop of new pilots present. First hand accounts of his off-duty antics, including knife throwing into the door of the ad-hoc officers mess while waiting for dinner to be served, give some insight to his character, and caused one English officer to become convinced that Stanley was a born and bred North American. Reading between the lines of what brief recollections his contemporaries wrote of him one cannot help but sense an admiration for his wild mannerisms and japes. Although recruited and trained on equal lines with those around him, it was clear that he possessed qualities to which younger men were attracted and were willing to follow. Stanley always sat at the head of the table in the officers mess.

To War

On 23 July Stanley and his colleagues flew their Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c two-seat biplanes (Fig.3) across the Channel. The BE2c variant was controversial. It had been developed to be inherently stable which was helpful for artillery observation and aerial photography duties, and it had a relatively low accident rate. However, stability was achieved at the expense of manoeuvrability, while the observer in the front seat ahead of the pilot had a limited field of fire for his gun.

As the pilots soared across the water, the ground support elements experienced a less flamboyant journey as recounted by mechanic Ira Jones – It took us three days to get from Havre to our base at Choques, near Bethune. We rumbled in lorries over interminable straight French roads. Through the lines of poplars in full leaf we could stare at fields apparently untouched by war. We seemed to be getting nowhere. Then, in the afternoon of July 25, somebody said ‘There’s the aerodrome!’ Eagerly we looked over the side of the lorry. On the left of the road was a bare black patch of cinders, about 300 yards square, fringed by three canvas hangars. There was not a plane in sight, nor a figure moving. Even in the bright sunshine, the place looked forlorn and deserted.

Over a bank of trees behind the aerodrome shone the white turrets of an ancient chateau – the first I had seen outside picture books. This, I discovered later, was to be Squadron HQ and officers mess (Fig.4). The lorries rolled on past the aerodrome, turned right down a narrow lane and came to rest in the yard of a tumbledown farm. The farmer, his wife and their pretty sixteen-year-old daughter waved and cheered from the door of the house as we pulled in. The daughters’ greetings were returned with particular fervour. I had visions of a nice quiet bed in a room under that lichened overhanging red roof. Instead, we were marched off in flights to the different outbuildings. My billet that night was a palliasse on the floor above the cow byres. It was clean enough, but somewhat strongly scented. Dumping our kit, we got busy immediately on the job of going into occupation. The aircraft flew in from another aerodrome within a couple of hours of our arrival. By nightfall, 10 Squadron was operational.

10th Squadron’s role was to be that of observers for the Royal Artilley.

Lieut. William Hodgson Sugden-Wilson (Fig.5) was coupled to Stanley as observer and gunner. Sugden-Wilson was also a pilot, having achieved his aviator’s certificate at Farnborough in April, two months behind Stanley who flew as his senior. Hailing from Elland in Yorkshire, he had been attracted to the Flying Corps after service with West Somerset Yeomanry Territorial Force.

On the morning of 21 September 1915 Sugden-Wilson clambered into the front observer’s seat with Stanley behind him at the controls. Their task was to spot for the guns of the Royal Garrison Artillery for which a two-week familiarisation had been conducted to confirm methods of communication and aerial techniques. Sugden-Wilson had experienced a close shave eight days earlier flying with a different pilot when on reconnaissance over Lamain. A Fokker tore down from above and using its superior machine gun with interrupter gear pierced the BE2c’s petrol tank. Sudgen-Wilson replied with a whole drum of fire discouraging the Fokker from further harassment and the pilot was able to glide the torn aircraft towards Tournai and a safe landing.

As Stanley directed the BE2c smoothly into the sky, across the battle lines to the east so did Max Immelmann. By September 1915 Immelmann, who had been flying since the previous November, had registered two kills in aerial combat and was later to be titled the Eagle of Lille, a much-admired pilot of Die Fliegertruppe des Deutschen Kaiserreiches, the German Army’s air arm. Ground crews at Choques saw Stanley and Sugden-Wilson disappear over enemy lines and went about their duties fully expecting the return of the exuberant Canadian-Caulkhead bursting with tales of derring-do.

Mild concern arose when Stanley’s aircraft became overdue and not in sight. This turned to worry and finally resignation as the light faded and the sun slowly sank from the empty sky.

Aftermath

Three days later Stanley’s father Douglas received a telegram advising that his son was missing, emphasising that this did not necessarily mean that he had been wounded or killed.

For many weeks letters of communication were sent and received by Stanley’s family from both his father Douglas and his sister Alison, the family of Lieut. Sugden-Wilson, and the military. During this period the military withheld the content of a telegram dated 23 September sent from Aeronautics GHQ in the field to Adastral House, London (derived from an abbreviation of the RFC motto Per Ardua Ad Astra – From Adversity to the Stars).

However, a letter written to the military by Alison Caws, suggests that some content of the telegram was leaked to the Press. At her home, St Catherine’s in Seaview on 28 September, Alison wrote – Dear Sir, I am writing to know if you can give me any information regarding the identity of the airmen mentioned in the enclosed cutting which was taken from the ‘Daily Express’ of last Thursday, Sept 23rd. On Friday last we received a telegram from you, stating that my brother, Lieut. SW Caws, Royal Flying Corps, has been missing since the 21st. We concluded that you were aware of the identity of the airmen mentioned here (always provided the report is true) or you would have told us – ‘missing, believed killed’. In any case, I should be deeply grateful if you could let us know for certain as soon as possible, and also if you have received any further information with regard to my brother.

The authorities were unwilling to confirm the status of any of the airmen. This changed when the parents of Lieut. Sugden-Wilson, received a letter from him on 15 October, despatched from a prisoner of war hospital in Germany.

Referring to the events of 21 September, he wrote – When we were 11,000ft. up we were attacked by two hostile machines. Lieut. Caws who was the pilot, was shot dead; the bullet passing through his neck downwards to his heart, passing through the instrument board and hitting my leg. I went on fighting till I had no more ammunition left, but by this time the aeroplane was in a spinning nose dive. I had to get the machine under control before we hit the ground. The machine at once caught fire, and before I got out of the wreckage my boot was burning fiercely. I was able to get it off quickly, but not before my leg was slightly burned. I then tried to lift the dead pilot out, but he was too heavy, both his legs having been broken in the fall. My face was burned a little when I tried to get him out, but my right leg was useless, and I could not stand any longer, so it was no good. The remains of Lieut. Caws were buried by the Germans with military honours, and they were very kind to me, and looked after me well. We had a great fight lasting fifteen minutes. My back and legs are progressing as well as can be expected. Up to the present I have been in four different hospitals, and am as cheerful as my position permits.

Wilson-Sugden’s letter confirmed that Stanley had been Max Immelmann’s third kill, which was to be followed by many more. Such was the mutual respect between the pioneering aerial combatants that Immelmann was to visit Sugden-Wilson while in hospital.

Left - Max Immelmann and an artists recreation of the airmen's ace manoeuvre involving a roll inside a loop.

Research revealed Max Immelmann’s diary entry in which he alternates between the past and present tense to describe the events that happened on the day of his twenty-fifth birthday.

On September 21st, my birthday, I took of at 9 a.m. in my Fokker monoplane. I had no special orders, but wanted to protect a machine of our section which was putting our artillery on to newly located objectives by telegraphic signals. These artillery fliers are often disturbed by enemy fighters and must then retreat, because their weapons are automatic carbines.

So I made arrangements with the crew of the other machine about the spot where we shall cruise. At 9.45 a.m. I fly my circles over Neuville village, as agreed. I am 3,100 metres up, and cannot see the other machine, which has arranged to climb to 2,500. That does not matter; it will certainly be there. The only trouble is that I cannot see it; probably masked by my wings. I go round and round, for a whole hour. The business begins to be a bit boring.

For quite a long time I have been looking out on my right; when I peer out to the left again, I see, quite close behind me on my left, a Bristol biplane which is heading straight for me. We are still 400 metres apart.

Now I fly towards him; I am 10-12 metres above him. And so I streak past him, for each of us had a speed of 120 kilometres an hour. After passing him I go into a turn. When I am around again, I find he has not yet completed his turning movement. He is shooting fiercely from his rear. I attack him in the flank, but he escapes my sights for a while by a skilful turn.

Several seconds later I have him in my sights once more. I open fire at 100 metres, and approach carefully. But when I am only 50 metres away, I have difficulty with my gun. I must cease for a time. Meanwhile I hear the rattle of the enemy’s machine gun and see plainly that he has to change a drum after every 50 rounds. By this time I am up to within 30 or 40 metres of him, and have the enemy machine well within my sights. Aiming carefully, I give him about another 200 rounds from close quarters, and then my gun is silent again. One glance shows me I have no more ammunition left. I turn away in annoyance, for now I am defenceless. The other machine flies off westward, i.e. homeward.

I am just putting my machine into an eastward direction, so that I can go home too, when the idea occurs to me to fly a round of the battlefield first, for otherwise my opponent may think he had hit me. There are three bullets in my machine. I look round for my ‘comrade of the fray’, but he is no longer to be seen. I am still 2,500 metres up, so that we have dropped 600 in the course of our crazy turns.

At last I discover the enemy. He is about 1,000 metres below me. He is falling earthward like a dead leaf. He gives the impression of a crow with a lame wing. Sometimes he flies a bit, and then falls a bit. So he has got a dose after all. Now I also drop down and continued to watch my opponent. It seems as if he wants to land.

And now I see plainly that he is falling. A thick cloud rises from the spot where he crashes, and then bright flames break out of the machine. Soldiers hasten to the scene. Now I catch my first glimpse of the biplane I intended to protect. It is going to land. So I likewise decide to land, and come down close to the burning machine. I find soldiers are attending to one of the inmates. He tells me he is the observer. He is an Englishman. When I ask him where the pilot is, he points to the burning machine. I look, and he is right, for the pilot lies under the wreckage – burnt to a cinder.

The observer is taken off to hospital. I fly off again, to the accompaniment of rousing cheers from about 500 soldiers. When I reach home, the men of the section lift me out of the machine and carry me on their shoulders to my tent with loud hurrahs.

Later on I visited the prisoner in hospital. He told me that I had hit the machine many times without doing too much damage until at last I killed the pilot instantaneously with a shot through the neck, whereupon the machine fell. When it crashed, it took fire, and he was hurled out in a high parabola. That saved his life, and he only sprained his feet and back.

He said he fired about 400 rounds and was astonished at not hitting anything. That is more or less the picture of an airfight.

Immelmann stood alongside the wreckage of Stanley's aircraft.

The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force includes the following extracts.

Stanley Winther Caws was the first Canadian airman to be killed in action. Caws was Canadian by choice, having been born in the Isle of Wight, and, at thirty-six, was unusually old to be flying in the RFC.

Another RFC candidate remembered him thus: ‘Barely had we been shown to our rooms when a strikingly good-looking man made his appearance, grinning, and asked us if we were the two ‘new guys’. In an obviously Canadian accent, he welcomed us to Brooklands. A grand character, the life and soul of our little party, he was always with us to give advice where it was needed. Caws always sat at the head of the table in our little mess room in the Blue Anchor, and I can hear him now, saying grace when the maid had served dinner on the night of our arrival. It was a solemn little utterance that went like this ‘For what we are about to receive, may the Lord make us truly thankful, and see to it that we have the strength to keep the god-damned stuff down!’ He had the disconcerting habit, while we were waiting for the next course to be brought in, of suddenly snatching up any table knives within reach, and slamming them, one after the other, into the woodwork of the door.’

Manners were more stereotyped in 1915 and a man like Stan Caws must have impressed the sheltered eighteen-or twenty year olds with whom he was thrown into such close contact. Perhaps his peculiar social graces help to explain how Canadians in the RFC got their reputation for unorthodoxy and mild rowdyism in a service where unorthodoxy and mild rowdyism were way of life.

Stanley was no Canadian by birth but was a frontiersman and pioneer in spirit and he is remembered on several memorials across the country, notably the National War Memorial in Ottawa, in addition to those on the Isle of Wight and Arras, France.

The according of full military honours by the Germans at Stanley’s burial, close to where his aircraft struck the ground, is recorded in several documents. Unfortunately, the precise location was not. A further three years of the world’s most terrible warfare, with front lines ebbing and flowing across a landscape altered irrevocably by bombs, bullets and boots, rendered the grave untraceable. Stanley remains where the Germans placed his body, unmarked and undiscovered to this day.

His father Douglas passed away at the Westwood Nursing Home, West Street, Ryde, in October 1932. Harriet’s death followed twelve months later.

Stanley’s eldest sister Dora never left the Isle of Wight and appears to have never married, serving most of her life as a midwife. She passed away at Upper Orchard, Seaview, in February 1948.

His close friend, Fernand Charles Butler, remained with the 19th Alberta Dragoons, redesignated 'A' Squadron, Canadian Corps Cavalry Regiment, CEF, when they were deployed to France in the same month that Stanley transferred to the RFC. Given their strong friendship and close association following war in South Africa, their Canadian adventures both in and out of uniformed service and transatlantic crossing with the CEF, a protracted separation seemed unlikely. Fernand endured seven months in the trenches before an unsurprising transfer to the RFC, eight days before Stanley’s death.

Fernand survived the war, met, fell in love, and married Stanley’s sister Hilda (Fig.6) in Calgary in 1919. Hilda evidenced a similarly pioneering spirit, passing both the minor and major examinations in pharmaceutical chemistry. For a woman to achieve this prior to the First World War was ground-breaking. In 1912 she was among the few that strove to advance female professionals by establishing the Association of Women Pharmacists. Appointed as the association’s first treasurer, Hilda fulfilled the role for many years until emigration and married life on the Canadian frontier.

Fernand passed away prematurely, aged 53, at Camrose, Alberta, in December 1934. Hilda, four years his senior, returned to the Isle of Wight and passed away in 1967.

Of Stanley’s younger sisters Constance married in 1914 and after the war set up home with her husband in Norfolk. She passed away in 1983 in Lincolnshire at the grand age of 96 and had visited Canada just once, in 1959.

Youngest sister Alison, who had just turned twenty when Stanley was reported missing and who wrote pleadingly for information, sailed aboard the SS Medina as a chemist, departing London bound for Port Said, Egypt, on 1 September 1916. In 1920 she married Robin Edwin Steward in Alexandria. They returned to England and established home at St Faith’s and Aylsham, Norfolk where they raised two children. She passed away at Dallington, East Sussex, on 20 March 1967.

Memorial plaque inside St Helen's New Church, Isle of Wight. The plaque incorrectly states 'RAF' which wasn't formed until 1918, Stanley Caws was a pilot of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Also the citation is at odds with all known records and is invalidated by the content of first-hand accounts written by both his observer Lt. Wilson-Sugden, and that of German ace Max Immelmann. Caws was engaged by a lone aircraft flown by Immelmann, and did not shoot down another aircraft.